Isabel Robbins: Our Family’s Youngest and Most Devoted Gastronome

I come from a family where the line between being a foodie and being a glutton is heavily blurred. We have lots of eager eaters of all stripes, but the only one who can “hit for the cycle” – cook, travel, ferret out the newest hotspots and discern obscure ingredients – is my niece Isabel. She’s 12, the youngest of my brother and sister-in-law’s three children.

Isabel was born in Tokyo, lived there until she was 18 months old and now attends an international school. The combination of nature plus nurture has provided her with a certain fearlessness when it comes to eating – when other kids her age were subsisting on a diet of mac and cheese and chicken nuggets, she could not only pronounce “Izakaya,” but she could also parse the menu at one.

There was no question that food meant a lot to her early on. One story that’s entrenched in family lore is the time when she was about two that we all ate at an outdoor restaurant with a fountain. It was blazing hot, and the kids were permitted to jump in and out of the water. Isabel wanted to play – indeed, wanted to be like the big kids – but she also had the self-assurance to know that she didn’t want anyone else eating her food. She’d run to the fountain, dunk herself, run back to the table and wag her finger at us and say, “Don’t touch my tandwich!” Lather, rinse, repeat.

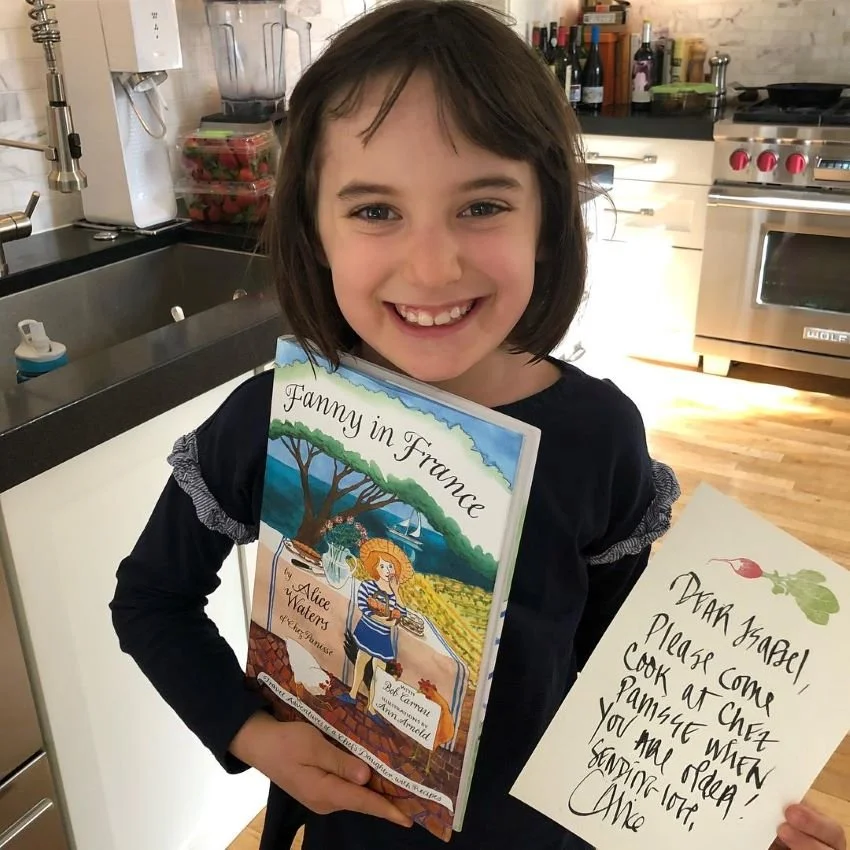

As time went on, though, sandwiches remained in the picture but they weren’t enough. She started to cook seriously, and solicited advice from the likes of Alice Waters and Samin Nosrat. Every time I walked into their house she was either standing over the stove, immersed in a cookbook, or plotting the next foodie adventure. During COVID, she gave the executives at my brother’s multinational management consulting company a Zoom tutorial on how to make gyoza. She recently led my foodie parents, her grandparents, on a gourmet adventure through Chicago.

While Isabel does not fish (I fell far from the tree on that obsession), food is an important part of the fishing travel experience – and Isabel has more international eating experience than most of our readers, and likely more than me and Hanna. I figured it was time to get her thoughts on the topic in ink before she was too busy as a chef or food critic to have time for us. Here’s her story, in her own words:

HPFC: You’ve been to more countries than most adults. When did you truly realize that food travel and cooking were an important part of your life?

Isabel: I think it was when we went back to Japan a few years ago. I remember having soup dumplings in Roppongi Hills that I hadn’t had in a really long time and they were really good. At that point I realized that the food around the world is so good and I wanted to experience it all.

HPFC: So many kids just like chicken nuggets and macaroni and cheese. Did being born in Japan and spending your first few years there was a big part of why you are such an experimental eater?

Isabel: I think it runs in my family, but another part of it is that when we moved back from Japan my parents continued to feed us Japanese cuisine because we learned to love it in Japan.

HPFC: So when you go to Japan now, what are the things that you crave and want the most?

Isabel: The tempura and the soup dumplings – because the soup dumplings in America, the dough is way too thick. And it’s the same thing with the tempura. It’s way too doughy.

HPFC: So is Asian cuisine your preferred choice to eat and cook, or is there greater variety in your palette?

Isabel: I think Asian cuisine is a large part of my interest, because the majority of the places I’ve traveled are in Asia, but I’ve had other foods around the world that I also really liked. When we went to Mexico, the food there was really good.

HPFC: How many countries have you visited?

Isabel: I counted recently and I seem to remember it was either 17 or 18.

HPFC: Other than Japan, which ones have been your favorite food experiences?

Isabel: I think maybe Mexico. We were in San Miguel de Allende, which is a really pretty smaller city, and then we also went to Mexico City.

HPFC: What were some memorable dishes or meals that you had there?

Isabel: In San Miguel de Allende I remember that we had a breakfast buffet with a lot of traditional Mexican meats that were really good, and then in Mexico City we took a cooking class and we made these cactus tacos and mole and they were so good.

HPFC: What are some of your favorite things that you’ve cooked so far?

Isabel: With my mom I make dal, which is an Indian lentil soup. That’s really good. I also like making gyoza with my dad. When COVID started we were giving cooking classes online on Zoom for my school, and then my dad asked, “Why don’t you do one for my company?” and so we made miso soup and gyoza.

HPFC: Do you think that going to an international school has expanded your food horizons?

Isabel: I like to go over to my friend’s house. She’s Iranian, and I’ve had a lot of Iranian food over there. One of the things is a split pea stew that her grandma makes.

HPFC: We know a lot of people who’ve never been out of the United States. What are some of your favorite food experiences you’ve had in the US?

Isabel: Well, it’s Japanese again, but we really like to go to Izakaya Seki here in Washington. The owner there he made us this special soup with noodles and other ingredients and it was really good, but then he also took the leftover broth and put rice in it. It was super-good.

HPFC: Are there foods that you don’t like or won’t eat?

Isabel: Not really. I don’t like peanuts or peanut butter – really anything with peanuts.

HPFC: Every other kid in the world likes peanut butter and jelly and you prefer Japanese stew?

Isabel: Yeah. There are other foods that I dislike, but I won’t refuse to eat it. For example, I don’t like eggplant a lot, but if someone serves it to me in something I’ll usually eat it.

HPFC: What did you try when you visited Iceland last year?

Isabel: I didn’t try this one, but my dad had smoked puffin. We all had fresh cod that we caught fishing.

HPFC: So do you want to join us on a fishing trip?

Isabel: Sure.

HPFC: You don’t sound too convincing. You just came back from Peru. What was the cuisine like there?

Isabel: We had Nikkei, which was a mix of Japanese and Peruvian food that was really good. We also had a lot of ceviche there. I didn’t know that was going to be such a huge thing. Some of it had a weird aftertaste and my stomach felt a little weird, so I wasn’t always hungry.

HPFC: What other countries do you still want to visit and try their food?

Isabel: I really want to go to New Zealand to see the sheep. My dad said that there are a lot of sheep.

HPFC: Do you know what they eat in New Zealand?

Isabel: I don’t.

HPFC: Do you think you’ll pursue a career in food?

Isabel: I don’t think so, but I’ll always find it really interesting.

HPFC: Are you a better baker or a better chef?

Isabel: I find myself baking more often but it depends on what I’m making. I bake alone more often, and I like that a lot. I like to bake red velvet cake and cookies. I used to make ice cream, too.

HPFC: Did you eat guinea pig in Peru?

Isabel: My dad, and my sister Madeline and my brother Tai ate guinea pig gyoza. They said that they just tasted like chicken. I was going to eat it and then I just decided not to.

HPFC: What’s your dream meal? If you were on death row and could choose one last meal what would it be?

Isabel: That’s tough. There are so many good things to choose from. I think it would be a Thanksgiving meal, but not turkey. I’d want stuffing and corn pudding and cranberry sauce and sweet potatoes with marshmallows and a slice of pumpkin pie with whipped cream on top.

*************************************************************************

Isabel’s Notes and Recipes for Some of Her Favorite Japanese Foods

History and context of gyoza

Gyoza is the Japanese pronunciation of jiaozi

There are a few theories of where the name “jiaozi” originated. One of the most popular theories is that jiaozi was named because of its unique horn shape since the Chinese word for “horn” is jiao.

Jiaozi are rumored to be invented by a Zhang Zhongjing, a practitioner of Chinese medicine to treat frostbitten ears. He would boil lamb meat, peppers, and medicines in a pot and then wrap the filling in small dough wrappers. He then used them to warm poor people’s ears who did not have sufficient clothing or food in the winter. Overtime, Zhang Zhongjing’s recipe was adapted and imitated by the people of China.

Japanese soldiers became familiar with jiaozi during World War II when they were quartered in China. When the soldiers returned home to Japan they wanted to recreate jiaozi and thus the gyoza was born.

The prevalent differences between Japanese-style gyōza and Chinese-style jiaozi are the rich garlic flavor, which is less noticeable in the Chinese version, and that gyōza wrappers appear to be consistently thinner,

Served at ramen shops, Chinese restaurants, izkaya (casual dining establishments) and a small number of gyoza specialty shops.

Types of gyoza: yaki, sui, age

Miso soup history

Three-quarters of Japanese citizens consume it once a day.

A miso paste that has been fermented for a longer period of time, such as a red miso, gives the miso soup a stronger, deeper flavor. A miso paste that has been fermented for a shorter period of time, such as a white miso, provides a lighter, sweeter flavor.

More than 80% of Japan's annual production of miso is used in miso soup, and 75% of all Japanese people consume miso soup at least once a day.

During the Asuka period (592 – 710) China introduced to Japan a food called hishio, something made of soybeans and salt. Later, the Japanese made it into a paste form: miso was born. At the time and until the Heian period (794 – 1185), miso paste was not yet used in soup, but was eaten much like a popsicle!

The ichiju-issai style of preparing food became common among the samurai society during the Kamakura period (1185–1333), giving birth to the custom of serving miso soup with everyday meals.

During the age of civil wars in Japan, miso soup was used by military commanders as a field ration. There was even an ancestor to today’s instant miso soup, which was prepared by simmering the stem of a taro root with miso and then drying it out. Soldiers chopped it and put it in hot water to transform it into miso soup.

Regional differences: red vs. white, onions, adding in ingredients, homemade miso vs. store

Miso is made from fermented soybeans, it is full of varied nutrients, and it has mainly two properties: it contains all the amino acids needed by human beings and is therefore a great source of proteins; it is also a source of probiotics, the good bacteria in your digestive system.

Actions

Prep

Chop all the veggies

Put Konbu in early

Make some dumplings

Introduce all the ingredients for two stations

Miso soup:

Konbu, Katsuo, Miso paste, Wakame, Tofu, Green scallions

Pot, Colander

Gyoza:

Protein, chives, mushrooms, onions, garlic, ginger, cabbage

Soy sauce, Rice vinegar, sesame oil

Mixing bowls

Miso Soup

Ichiban Dashi

Get the konbu into the water first (20-30 mins)

Add Katsuo flakes and bring to boil, only boil briefly, let sit 2 mins

2 cups per 4.5 cups of water

Drain via cheesecloth

Add miso

1 tbps per 2 cups of water

Red miso paste if you like your miso soup very smoky and salty, white miso paste if you prefer a milder, gentler, and sweeter taste, and awase miso paste if you like it in between

Place the miso paste in a colander and lower it into the pot until enough water covers the miso paste.

Using chopsticks, swirl the paste until it completely dissolves into the soup.

Dumplings

Make the filling

Protein

Mushroom, cabbage, chives,

Ginger, garlic

Soy sauce, rice vinegar, sesame oil

Make the dumplings

Cook first 1-2 minutes in sesame oil

Then 1 cup of water with 1 tbsp of flour

Steam for 5-6 minutes or until water evaporates

Dipping sauce

2:1 soy to rice vinegar

1 tsp sesame

Add a little ginger